1 of 3Trainees with MTS's Underground Mining Program have an opportunity to work onsite with a mentor by their side. — Bill Braden photo courtesy NWT

1 of 3Trainees with MTS's Underground Mining Program have an opportunity to work onsite with a mentor by their side. — Bill Braden photo courtesy NWT Mine Training Society

2 of 3The Mine Training Society's Diamond Driller Helper Program was a partnership between MTS, Avalon, Peak Drilling and Aurora College. — Bill Braden photo courtesy NWT Mine Training Society

3 of 3Trainees with MTS's Underground Mining Program utilize a $1.5 million state-of-the-art simulator funded jointly by BHP Billiton, Rio Tinto and De Beers. — Bill Braden photo courtesy NWT Mine Training Society

By 2017 it is estimated that the three northern territories of Canada will require more than 9,000 new miners. Bearing in mind that for every one mining job there are three service jobs that surround it, the requirement rises to encompass another 27,000 individuals. That level of demand means looking at staffing issues from a whole new vantage point.

“We’re actually working on a pan-territorial strategy to try and meet the needs of the North,” said Hilary Jones of the Mine Training Society (MTS) in Yellowknife. “All three territories came together on October 13 in Yellowknife and have started working with one another to develop a Northern natural resources workforce development strategy.”

Recognizing that the mining jobs of today are no longer the pick-and-shovel variety of the past, Jones said that as many as 78 per cent of available mining positions are considered to be skilled or semi-skilled positions, with less than five per cent of the needed workforce falling into the non-skilled labour category. Her job, said Jones, is to ensure that local Aboriginal Peoples and other northern hires are trained and ready to assume those positions.

“Because ideally we want to source as many of those jobs as possible locally,” said Jones. “There’s unemployment and then there’s people who are not in the labour force. The mining industry today has become a very sophisticated workforce and the avenue is no longer there for the uneducated, untrained or unskilled individuals to get into the industry. So we not only have to work with the people in our communities, but we also need to go into the schools and encourage students to stay in school and get their high school graduation with the right courses, so that they can take advantage of the many job opportunities in the mine.”

What may seem like a daunting task at the outset is one that the Mine Training Society has been laying the foundation for over the past 10 years with its community-based training programs.

While the lure of working in the mines and the higher income potential it brings is very appealing, a career in mining isn’t for everyone. Finding that out sooner rather than later can go a long way to ensuring satisfaction for both employee and employer.

It’s for this reason that Jones said that, after earlier experiments with doing initial training at the mine site, MTS now uses community-based programming.

“Transitioning people slowly, right from within their home community, means they have the support of their family,” said Jones. “They haven’t just been taken away and thrown into a larger centre, which has already been proven to have lower success rates.”

She’s talking about programs such as Aurora College’s Ready to Work North and the MTS’s Introduction to Underground Mining, as well as support from sharing circles, counselling and mentors.

“Taking into account people’s level of comfort with the training, recognizing the value of traditional knowledge, and respecting the unique traditions of the North,” said Jones, “helps to bridge the cultural gap and create a successful learning and working environment that takes a holistic approach to dealing with students, instead of simply dealing with their learning needs.”

Using the tenets of the medicine wheel, which looks to the four quadrants of an individual-- the mental, the emotional, the spiritual and the physical--MTS training tries to ensure balance is kept within those four quadrants throughout the process.

“There’s always a person in their corner, so to speak,” said Jones. “And the success rate from that is phenomenal.”

It’s a model that is now being exported to the Yukon, Nunavut and northern B.C.

“After more than 10 years we’re kind of like the grandma in this business,” said Jones. “We have all these sort of ducklings out there that have followed our community-based training path. It works really, really well, especially with engaging aboriginal communities.

Jones explained that the training societies or the mine training organizations are part of the supply and demand chain.

“We work with industry to determine what their training needs are and then we go out and find the potential employees and train them,” she said. “By utilizing community-based training, we now have a reputation in the communities as a place of trust. If you come with us and we train you, you can get employment.”

It’s a level of trust that, with the help of the pan-territorial partnership, will ensure real opportunities for northerners.

“No one can go it alone here in the North, because we are so small in terms of population and so big in terms of jurisdiction,” said Jones. “So in order to be able to do something you really do have to develop those partnerships. Everybody chips in a little and you get a whole bunch and it saves duplication of effort.”

When Tony Whelan, an employee with De Beers’ Snap Lake Mine, was called to the surface, he had no idea he was soon going to witness the birth of his first child.

Whelan, a recent graduate of the MTS Underground Mine Training Program, had established a good relationship with the organization and with De Beers. When Whelan’s girlfriend called the mine to tell him she was in labour, the De Beers management team made sure Whelan was brought to the surface, thrown on a plane, and was by his girlfriend’s side with plenty of time to spare.

“He got here (Yellowknife) I think at 4:00 in the afternoon,” said Jones. “The baby got here around 8:30 at night and at 8:30 the next morning he was at our door, showing us pictures of the baby, and back on a flight to the mine by 2:30 p.m.

“That’s the level of support they get from the mines here, because family and community are very important here in the North,” continued Jones. “With a funeral of an elder in a community, the community is expected to be there, and in trying to work with that, trying to work with those kinds of family issues, the mines are trying to be as flexible as they can.”

Author

Gail Jansen

Filed Under

Related Stories

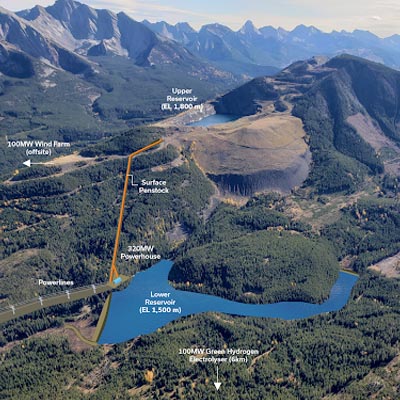

Tent Mountain green energy plan: triple solution

3 years ago

Gold miner Mitch Mortensen is the perfect advocate for placer mining in B.C.

3 years ago

The Association of Mineral Exploration leads through change

4 years ago

$500,000 federal funding to help promote northern mining at annual conference

6 years ago

PDAC 2020 awards honour industry leaders

6 years ago