The future is here

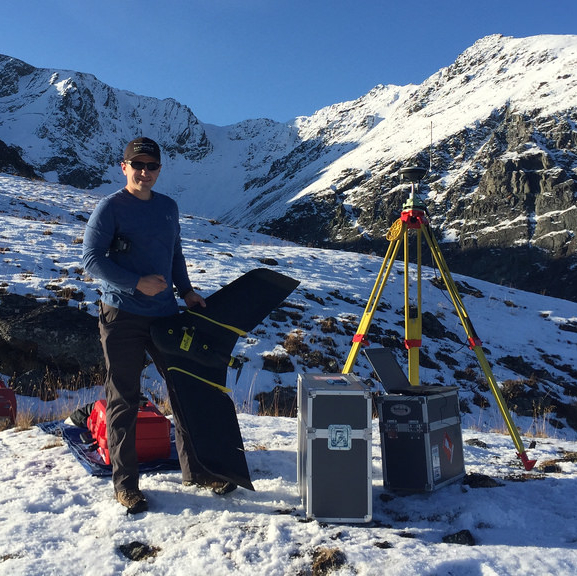

Peter LeCouffe, operations manager, holding the new RTK fixed-wing drone next to a GPS base station. — Photo courtesy Harrier Aerial Surveys Regardle

Peter LeCouffe, operations manager, holding the new RTK fixed-wing drone next to a GPS base station. — Photo courtesy Harrier Aerial Surveys

Regardless of the project in question, “a good starting spot is always a good map,” said Peter LeCouffe, operations manager and co-founder of Harrier Aerial Surveys. Harrier Aerial Surveys is a licensed commercial unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) remote sensing service provider. The company's drones collect aerial imagery to create digital elevation models and three-dimensional maps.

Harrier attracts clients across a range of sectors, all with specific questions that need answers. “It’s a lot of problem solving. No two operations are the same,” said LeCouffe. In mining, Harrier creates 3D data sets that can be used to measure anything onsite—“from volume calculations to planning future developments of a project,” he said.

While LeCouffe was completing his bachelor's degree in Geographic Information Systems (GIS), he worked on a project with Robert Simmerling through Simmerling’s laser scanning company based in Nelson, British Columbia.

“Most of GIS at the time was 2-D data, looking flat down on the Earth versus vertical components of it as well,” LeCouffe said. “I was curious about 3-D data.” Simmerling and LeCouffe discovered a similar interest in drone use for 3-D data collection.

LeCouffe and Simmerling combined their expertise under the name of Harrier Aerial Surveys. “We use my computer mapping background and his surveying and engineering background to create three-dimensional maps of survey grade accuracy,” LeCouffe said.

Harrier employees visit project sites to collect data themselves from scratch. They target their data collection based on the specific questions a client needs answered.

“For example, at the end of each quarter, one of our clients wants volume calculations of 50 different stockpiles on their property. We plan our flight based on the locations of these stockpiles,” said LeCouffe. Their results are tailored, accurate and ready for analysis. “Some of our clients are even engineers or GIS professionals themselves. We produce the raw data for them, and they produce the maps and analysis.”

Harrier uses modern photogrammetry to create its 3-D maps. Essentially, the company turns images into 3-D data. The digital model is derived from photographs. “Photogrammetry takes photos of the same object from different perspectives, then triangulates that object’s location in 3-D space,” said LeCouffe. “If you know where your camera location and direction is, you can draw a line from the camera centre, through that point in the image, off into 3-D space.”

The same process is completed from another camera directed onto the same object. A 3-D co-ordinate is assigned to the spot where those two lines intersect.

“If you do that for every pixel in each image, you end up with millions of points of the area you fly over,” LeCouffe said. The points describe the terrain, and the photographs are stitched together to create an orthophoto.

Drone data can be applied at every stage of a mine’s life. Harrier works with clients that need to summarize the minerals present at a prospective site, or are working on mine planning for permitting, all the way through to volume calculations of material stockpiles, and environmental assessments of reclamation and legacy projects.

No matter the stage of a mine, “the main thing that we like to communicate to our potential new clients is that a good starting point is always a good map,” said LeCouffe. “They spend so much money on exploring these prospective mineral operations, and to put all that together on a map with enhance the money you’ve already invested.”

At a recent project site, Harrier created an accurate digital elevation model and mapped out the GPS points of drill holes with survey grade accuracy. With the diamond drill data in an accurate elevation model, the company can dissect the mountain to project where the mineral layout is located. Harrier Aerial Surveys also recently created an accurate digital elevation model of six square kilometres at a prospective site six hours north of Terrace, British Columbia, for GT Goldcorp.

When comparing drone data mapping to traditional methods, the data is more accurate, but the resolution also aligns with a certain niche. “It’s a certain size project that benefits from drone use,” LeCouffe said.

Drone use has proven beneficial to mining. The technology is already accurate and discreet, and requires limited manpower. However, current drone technology already surpasses current regulations. Regulations limit how far they can fly, the sensors used, locations flown in, and times to fly are revisited.

Harrier Aerial Surveys is patiently waiting for the regulations to change. “We can conquer a lot more once these regulations open up,” said LeCouffe.