The struggles and spirit of Canadian coal mining towns

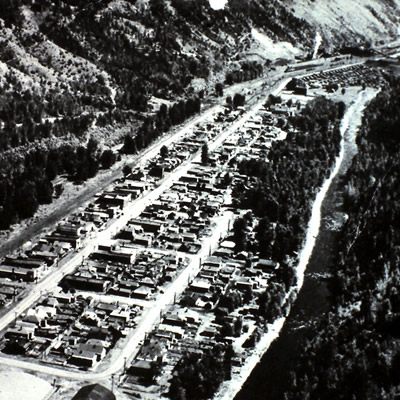

The twin towns of Michel and Natal were the original settlements in the Elk Valley. — Photo courtesy David Wilks Coal has been the livelihood of the

The twin towns of Michel and Natal were the original settlements in the Elk Valley. — Photo courtesy David Wilks

Coal has been the livelihood of the Elk Valley since its discovery in the late 1800s. Even today, most residents of Sparwood either work at the mines of the area, or are associated with the mines in some form. The Michel-Natal-Sparwood Heritage Society tells the story of the town’s growth and its relationship with the coal mines at the community museum.

The abundance of coal and the opening of the Crowsnest Pass Coal Company in 1889 brought families from across Canada, America and Europe to settle in the Elk Valley. Their cultures merged to create a special kind of community spirit and camaraderie that complemented the relationships of the men as they worked in the mines. The communities settled in two main areas: the small towns of Michel and Natal, adjacent to Highway 3 from Alberta.

As in most mining towns in the early years of coal’s reign, members of the community lived each day listening for the whistle to blow. Loss was a common occurrence. Conditions were dangerous, but because the men worked as contractors, they always went back underground for one more load.

The Elk Valley’s high quality coal, and the demand for coke, created additional hardships for the mining families. Coke is used in the production of steel. The mines of Michel-Natal used beehive-structured coke ovens to burn coal, transforming it into the sought-after coke. Unfortunately, early coke ovens created huge amounts of untamed smoke and slag. These particular ovens were built close to town.

“All of the people that lived there were very proud of Michel-Natal,” said David Wilks, president of the Michel-Natal-Sparwood Heritage Society. “It was a vibrant community.” Women took pride in the cleanliness of their homes, and even hung laundry to dry outside—despite the air pollution from the coke ovens. “They did their best to keep them clean outside, but it’s a coal mining town—that’s the way it goes sometimes.”

While the families of Michel-Natal were proud of all they had built for themselves, their extreme proximity to the coke ovens and other mine operations was eventually considered hazardous as safe mining practices evolved. Aside from the burden of the mine’s byproducts on the families, the government considered the area an unpleasant welcome to “beautiful British Columbia.” When travelling west on Highway 3 from Alberta, the first glimpses of British Columbia included Michel-Natal, the coal mine tipple and the coke ovens.

For these reasons, the Crowsnest Pass Coal Company and the Canadian government proposed an “urban renewal scheme” to the townsfolk in the early 1960s. The plan involved the relocation of Michel-Natal to the newly settled Sparwood, a few kilometres away.

The initial reaction to the plan was positive. However, over time, this positive reaction shifted to feelings of abandonment and frustration. The relocation plans took years to materialize. When they did, families were not granted appropriate compensation to move to the more expensive land plots in Sparwood. “It was probably one of the worst times for everyone there,” said Wilks. “It was unfortunate because they felt betrayed by the governments that had brought this on. They certainly were not provided with adequate recourse for their houses.”

Many families, discouraged by the lack of support and unable to afford new land in Sparwood, left the area altogether. As the towns of Michel and Natal were demolished, some of the fibres of the close-knit community were unravelled. Those who did move to Sparwood have worked together to restore their pride over the years. Wilks explained that many residents of Michel-Natal are still living in Sparwood today. They remember the old towns, and the move that disrupted everything they knew. “Their pride of community is second to none,” he said.

“There were a lot of old buildings there,” said Wilks. “But all of the land is owned by the coal company. They made the decision that everything was coming down. Unfortunately, there’s nothing left.” No signs of these two towns remain along Highway 3.

Learn more at the Community Museum

This is just a fraction of the complete story of how coal mining shaped these towns culturally and economically, and how the industry literally reshaped the land. To learn more, visitors are encouraged to visit the Community Museum in Sparwood.

The Michel-Natal-Sparwood Heritage Society recently moved the Community Museum to a new location near the Visitor Centre along Highway 3. The museum preserves the heritage of the long-lost towns of Michel and Natal.

“We want to show people what our history was like, and how we are going to move forward,” said David Wilks, president of the society.

The museum focuses on all the structures that were lost that tell the story of the community. For example, “one of the things that I think is lost in the Michel-Natal history is the old wood mill that was here as well,” Wilks said. While this wood mill contributed to the growth of the area, it was destroyed. Aside from the artifacts and stories on display in the museum, the Heritage Society hosts walking tours of the old underground mine machinery that is scattered throughout town.

Together, the Heritage Society’s collection gives visitors a glimpse into the rich mining past of Michel and Natal.

Learn more at the Community Museum

This is just a fraction of the complete story of how coal mining shaped these towns culturally and economically, and how the industry literally reshaped the land. To learn more, visitors are encouraged to visit the Community Museum in Sparwood.

The Michel-Natal-Sparwood Heritage Society recently moved the Community Museum to a new location near the Visitor Centre along Highway 3. The museum preserves the heritage of the long-lost towns of Michel and Natal.

“We want to show people what our history was like, and how we are going to move forward,” said David Wilks, president of the society.

The museum focuses on all the structures that were lost that tell the story of the community. For example, “one of the things that I think is lost in the Michel-Natal history is the old wood mill that was here as well,” Wilks said. While this wood mill contributed to the growth of the area, it was destroyed. Aside from the artifacts and stories on display in the museum, the Heritage Society hosts walking tours of the old underground mine machinery that is scattered throughout town.

Together, the Heritage Society’s collection gives visitors a glimpse into the rich mining past of Michel and Natal.