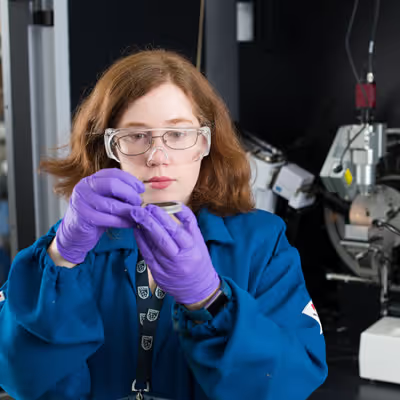

Rock Star Heather Kaminsky—“Queen of Clay”

Heather Kaminsky's team works with companies in the oil and gas industry to find solutions to their sustainability challenges. — Photo courtesy NAIT

Heather Kaminsky's team works with companies in the oil and gas industry to find solutions to their sustainability challenges. — Photo courtesy NAIT

Heather Kaminsky, lead researcher at the Centre for Oil Sands Sustainability at the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology (NAIT) in Edmonton, Alberta, helps the companies in the oil and gas industry find solutions to their problems with clay.

Inspired by a summer job in a lab after high school, Kaminsky chose to study materials engineering at the University of Alberta. She was quickly fascinated with microscopy and metallurgy especially. “I loved research, so I decided that I wanted to pursue graduate studies with Doug Ivey,” Kaminsky said. Ivey remained her mentor throughout the years.

“I wanted to do something that was relevant to Alberta, so I decided to study the mineralogy of the oilsands,” said Kaminsky. “In materials engineering, what you are taught is that if you understand the structure of something, you can understand its properties, then how to change the process to change the structure and change the properties.” She hoped to find solutions to the problems within oil extraction by applying what she learned while completing her bachelor's degree.

While studying, Kaminsky became interested more specifically in the microstructure of tailings. She was told that she needed to study clays as well if she was going to study tailings in the oilsands. Now, they call her the "Queen of Clay."

Kaminsky was not prepared for the difficulty clays would put in front of her. “I realized over the course of my PhD that clays were not simple,” she said. In fact, clays are a major challenge to the oilsands industry. “They were the antithesis of everything I learned in materials engineering.” The highly ordered structures she had learned about did not apply to clays.

The complication of clays is often avoided, minimized or simplified because no one wants to dive into their microstructure. Their difficulties have only become a focus over the past 20 years. They are present in only small amounts in the grand scheme of things, but they powerfully impact the extraction process.

“What I found when I started doing this work is that they were little but mighty," said Kaminsky. "They seem to control these massive processes.”

Clay plays a role throughout an entire mine. A muddy deposit can become slippery or unstable and thus difficult to manoeuver trucks through. Or, clay can cause choking issues when attempting to move through screens and filters. “In the extraction process, clays reduce the ability to extract bitumen,” said Kaminsky. "The more clay you have, the more difficult it is to separate the bitumen. Clays make the fluid that carries them more viscous,” she said, "like swimming through Jell-O versus water."

Finding solutions to these sorts of problems can be difficult. The obvious response would be to add water to dilute the effects of clay. However, adding more fresh water is wasteful.

Kaminsky worked in research and development throughout her career before landing at NAIT. She has worked with all clay-related problems over her career, but her current focus is on the impact of clay on tailings.

Clays are attributable to most of the fluid fine tailings that are present. Clays have a high affinity for water. “Even though they only make up 50 per cent of the materials in the fluid fine tailings, they take up 90 per cent of the water,” Kaminsky said. “There’s a lot of research now that links the volume of fluid fine tailings to the amount of clay and the level of activity of that clay.”

Kaminsky develops treatment methods for the fluid fine tailings. The questions she asks include: What type of polymers are most effective at binding these clays and getting them to collapse? How can we get a structure of our treated tailings that is geotechnically stable?

At the Centre for Oil Sands Sustainability, “we help bridge the gap between the innovators and fundamental researchers, and the industry,” Kaminsky said. “We understand how it is operational and how we can implement it.”

The Centre for Oil Sands Sustainability differs from a fundamental research centre because it has the tools to apply and test processes in-house with the help of industry sponsors. It creates solutions that the industry can implement as fast as possible. When a new method or tool leaves the centre, it is ready to work in the field. Kaminsky provides an industrial and technical background to come up with solutions that will stand up against industry challenges.

There are two requirements to begin research at the centre. “The first is that there is an industry client,” said Kaminsky. A company must be interested enough to pay for at least a portion of the costs. The industry sponsor could be an oilsands company or a technology provider. “The second is that there has to be some sort of research question.” The goal must be to validate, change or develop a new solution. The Centre for Oil Sands Sustainability works with oilsands operators and vendors—companies across the board with research questions.

Her team responds to industry needs within a short time frame. Their facilities and unique skill set can validate technologies in ways that the fundamental research community isn’t able to. Her team works to understand specific mechanisms and solutions, but also gives the industry the confidence that the mechanism would work over a range of situations. They help define the engineering parameters. They grow basic concepts to applicable solutions.

Drilling down

NameHeather KaminskyCompanyCentre for Oil Sands Sustainability, NAITQuotable“They call me the Queen of Clay.”